Ars pits the iPhone 6 Plus against $8,000 worth of pro gear to find out.

Our recent review of the Thrustmaster HOTAS Warthog joystick-and-throttle combo was notable not only for the really cool, really expensive piece of gaming equipment it featured, but also for the much-more-expensive full-frame DSLR used to take the article’s pictures: a $3,400 Canon EOS 5D Mark III.

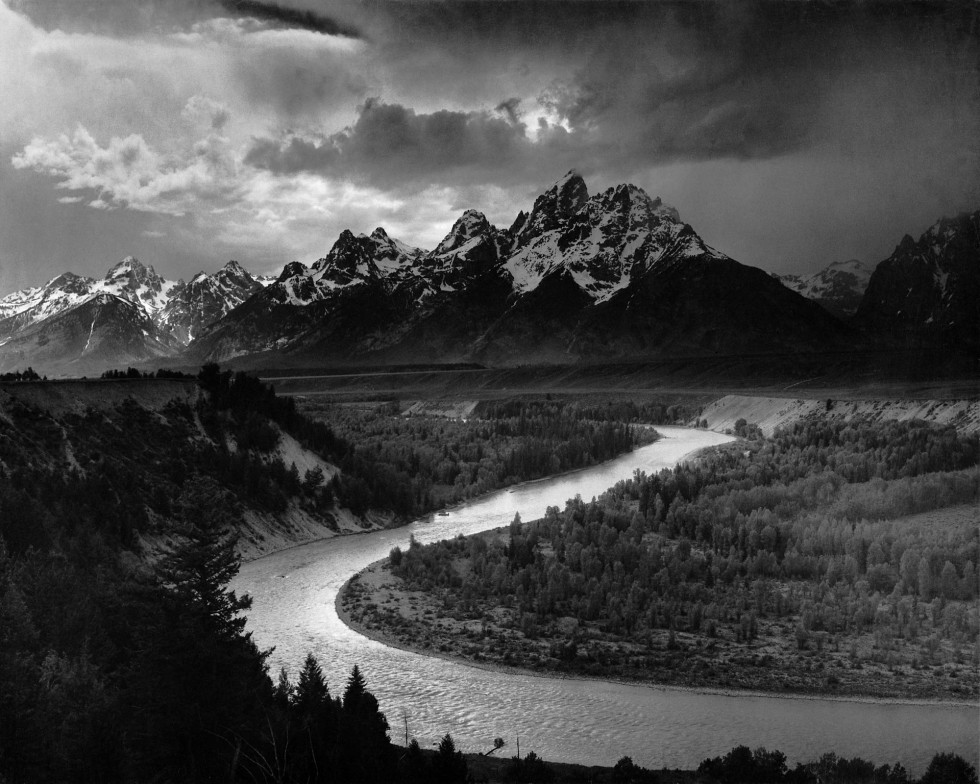

This is a fair amount of scratch to lay down for a camera, especially when the Internet is full of examples of pro photographers going the opposite direction, ditching bags of expensive gear in favor of smartphone cameras for most applications. The idea here is that the person, not the gear, takes the picture. And there is a (likely apocryphal) story that tells the tale of an encounter between famous novelist Ernest Hemingway and famous photographer Ansel Adams. In the story, Hemingway is purported to have praised Adams’ photographs, saying, "You take the most amazing pictures. What kind of camera do you use?" Adams frowned and then replied, "You write the most amazing stories. What kind of typewriter do you use?"Past a certain minimum point, skill trumps equipment when it comes to photography (and the same is true for almost any pursuit or profession). However, equipment does play a role—sticking two wildly different cameras next to each other and taking two pictures of the same scene will usually yield wildly different results. Those pro photogs whipping out iPhones instead of big DSLRs know a hell of a lot about how to make the most of the light they can get into a lens—and capturing light is what photography is all about—and they know how to maximize the strengths of their cameras under whatever shooting conditions they’re given.

It turns out that this is a really complex question to attempt to answer, but we’ve taken a crack at it, pitting our expensive 5D Mark III and fancy lenses next to the big new camera in Apple’s big new iPhone 6 Plus. The iPhone 6 Plus was picked over other smartphone cameras primarily because it's new and shoots great pictures—it's a great example of the best that smartphone cameras can be. We’ve done our best to snap some representative photography under several different lighting regimes, but there are so many variables to account for that it’s impossible to do a truly controlled test and comparison.

Rather than striving for tremendous accuracy and meticulously tweaking camera parameters, we sort of winged it, pointing and shooting with minimal settings adjustments and trusting the usually quite skilled automatic aids built in to both our smartphone camera and our DSLR. Because in real life, this is what the vast majority of casual photographers are going to do anyway.

The steep curve of learning

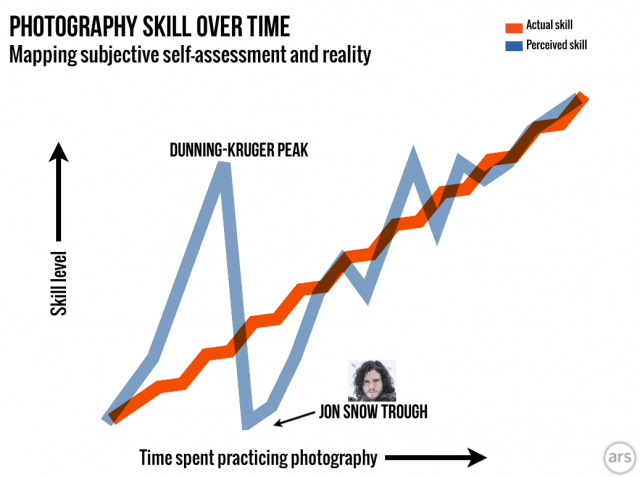

Learning how to take pictures is, like most skills, something that's easy to start doing, but difficult to do well. It takes time and practice—practice to understand the different parameters of a camera and how changing each affects the resulting image. As with most skills, knowledge is acquired often in fits and starts, a stair-step pattern of puzzlement and revelation. And as with most skills, a person’s subjective assessment of their skill doesn’t tend to track very well with their actual skill.

Only with a lot of time and effort can you realistically self-assess your skill. If I had to place myself on that chart, it’d be right at the second trough—I’ve learned, again, that there’s a lot I don’t know. But I am not anywhere near the same league as Ansel Adams, and I still have a fascination with gear and a reliance on technology to push me over gaps in ability. The genesis of this entire piece came from wondering what I’d do if I had to rely entirely on smartphones for product photography—and, frankly, I’m not sure I could do it. I need the extra techno-oomph to overcome lack of skill.

So enough navel-gazing and dithering about: let’s meet our two test cameras.

The contenders: iPhone vs. EOS

In one corner, we have Apple’s latest and biggest smartphone, the iPhone 6 Plus. The new iPhone’s camera has a scratch-resistant sapphire outer lens, a fixed f/2.2 aperture, fancy optical image stabilization to help make pictures clearer, and a 1/3" 8-megapixel sensor, which produces stills with a max resolution of 3264x2448 pixels. There are a number of other sites that have good breakdowns of some of the extra fancy technology Apple has crammed into the phone in order to make it take excellent pictures, but there’s a lot going on inside that little chunk of electronics. All told, a new iPhone 6 Plus will set you back at least $299 with a two-year commitment to a cellular carrier; off contract, the iPhone 6 Plus starts at $749 and rapidly goes north.

Before I started actually shooting photographs on a DSLR for Ars, I was totally bewildered as to why anyone would need more than one lens. After all, point-n-shoot cameras and smartphone cameras don’t have interchangeable lenses. What the hell is all of this heavy, expensive glass for? Fear not—we’ll explain.

For now, it’s enough to know that the gear here was all bought new, some by Ars and some by me. The total price for everything in this picture is a bit over $8,000.

Photographers out there are nodding their heads; most other folks are probably scraping their jaws up off the floor. Rest assured, though, this is a good-but-not-awesome collection of DSLR gear that pretty well matches my current photography abilities.

0 comments:

Post a Comment